Sun stand still

Celebrating the shortest day of the year

Besides the variety of enjoyable winter holidays we all look forward to each year, there’s one other date many of us think about. Around the 21st of every December, the Sun reaches its lowest point in the sky, which makes for the shortest day and longest night of the year. Why so important? Because from here on out, the days begin to get longer again as we look forward to sunnier, warmer days.

December’s Winter Solstice, whose rising point on this date shows in this view from our island house, is caused by Earth orbiting the Sun. The simplest way to put what this means, it’s the day of the year when the northern hemisphere is tipped away the most from the incoming rays of the Sun, leading to those very lopsided day and night hours.

It is also at this point where, after seeming to pause in its motion along the horizon for a few days, the Sun reverses and goes in the opposite direction. Actually, the word “solstice” means to “stand still” when translated from its original Latin.

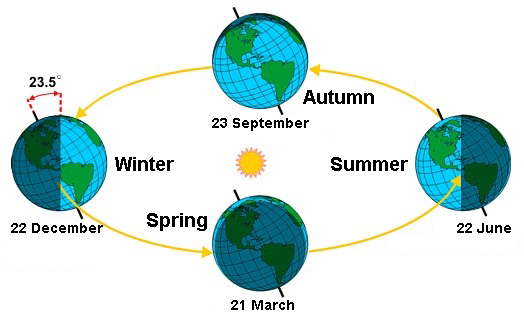

Classroom Earth globes are tipped over from being vertical for a reason: they’re mimicking the permanent 23½° tilt of Earth’s axis. It’s a common misconception our planet’s pole points in all directions as we orbit our star. It doesn’t, but is aimed at a fixed point in the sky, which makes sense if you think about it. For one thing, if it didn’t, then Polaris, also known as the Pole Star, wouldn’t be thought of as that at all. And all the other stars in the northern hemisphere’s night sky wouldn’t appear to go around it in circles like the concentric rings on an archery target.

Take a look at this simple diagram showing the relative position of Earth and Sun for each of the four seasons. It’s important to note that what this image shows: 1) it’s not to scale, 2) our planet’s orbit is much larger and is not circular, and 3) the Sun is not in the orbit’s center.

As already mentioned, and as seen in the diagram, Earth’s axis is pointing in the same direction for each of the seasons; towards that fixed point in the sky, which is very close to Polaris in the northern hemisphere. On the Winter Solstice in December (the Earth on the left), you can see how the northern hemisphere is tipped away from the Sun, so we get less light and energy from it this time of year. You can also see that below the equator the southern hemisphere is aimed toward it, so they are experiencing summer, the exact opposite of us. Could you ever imagine celebrating December’s holidays, but with the warmth and sunny days of June?

Is there actual evidence this is happening besides experiencing the seasons? It’s as easy as using our own eyes. In this montage I have combined the rising point of the Winter Solstice Sun on 21st December (over the island to the right), with the position to the left of both the Vernal Equinox (21st March) and the Autumnal Equinox (23rd September). Both are due east and approximately six months apart from one another. The left- and right-facing arrows show which way the Sun is moving relative to the horizon on these dates. From December through March it’s heading northward, while from September to December, it’s southward.

Like “solstice”, the word “equinox” also has a meaning when translated from Latin: “equal night,” a reference to the fact both days and nights are roughly each 12-hours-long at this time of year for a short period of time.

People often wonder, if it’s the shortest day of the year and we receive the least amount of our star’s energy, then why isn’t it the coldest time of the year? It’s a logical assumption to make, but it doesn’t take into account our planet’s atmosphere. It takes about two months for this loss of the Sun’s input to be felt due to atmospheric mixing. As a result, this means the coldest days for us up north after the Winter Solstice come in February.

Another misconception about winter is that it occurs when Earth is at its farthest point from the Sun in its orbit, but again, this season and the other three are all about our planet’s tilted axis. In fact, we’re at perihelion, closest to the star we orbit, in early 2026. On 3rd January at 18:00 Earth will be at a distance of 147,099,894 km.

Just for comparison’s sake, and something to look forward to, we’ll be farthest away, aphelion, at 18:00 on 6th July, and at 152,087,774 km; a difference of 4,987,880 km. But again, it’s not how far we are from the Sun making for longer, warmer summer days, but because Earth’s axis is tilted toward our daystar in the northern hemisphere.

By: Tom Callen