Far away and long ago…

The Webb space telescope continues to push boundaries

Ever since German-Dutch spectacle-maker Hans Lipperhey (c. 1570 – 1619) tried patenting what we know today as the refracting telescope in 1608, such instruments have become one of science’s most important and useful tools. The Italian physicist and mathematician, Galileo Galilei (1564 – 1642), turned his homemade telescope on the night sky in January 1610, which began forever changing our understanding of the many points of light seen in the darkness overhead.

Like most other things in world history, there were advances made in both telescope technology as well as in their size, which had led us to now having large examples in space. Above Earth’s turbulent atmosphere they can study the universe in unparalleled clarity and higher resolution, which includes using parts of the electromagnetic spectrum we can’t even see with our eyes. The two which are arguably the most famous are the Hubble Space Telescope (HST), launched into Earth orbit in 1990, and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). This second observatory reached its destination, a solar orbit near the Sun–Earth L2 Lagrange point, about 1.5 million kilometers from Earth, in January 2022.

Since JWST has begun active operations, it has been pushing the limits as to how far we are able to see into the universe’s past. As most of you already know, due to the distances of astronomical objects, the more distant they are the longer it takes their light to reach us. Two often cited examples are our own Sun, 8 light minutes away, and the Andromeda Galaxy, 2½ million light years distant. This means on any day we look, we see our daystar as it was 8 minutes ago, and this naked-eye galaxy 2½million years ago.

Astronomer’s best estimation for when the Big Bang occurred, creating the universe we observe today, was 13.75 billion years ago. One of the reasons large telescopes are built to use both on Earth and in space is to try and look for objects farther and farther away. The end result sought is to bring us closer to when this event took place.

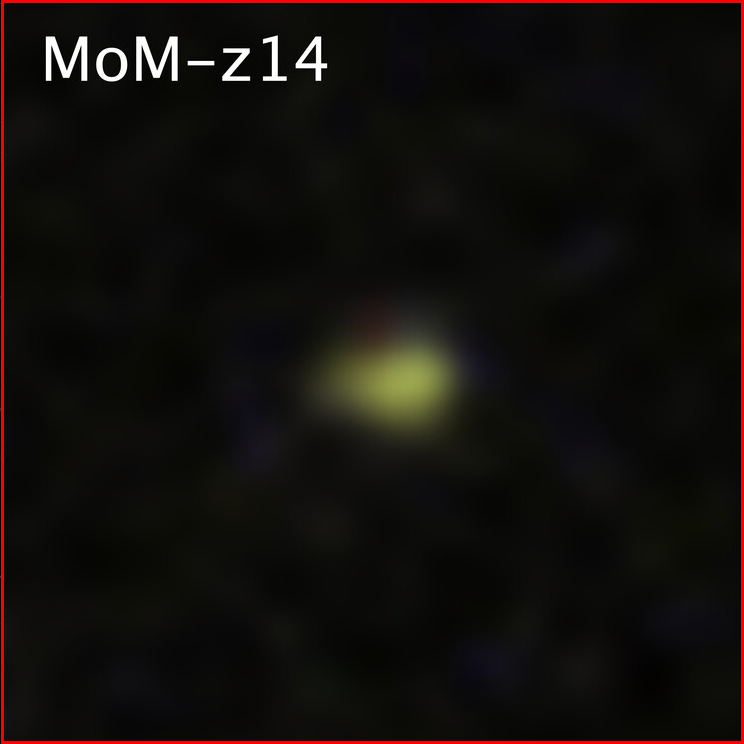

JWST has now observed an object so far away, a bright galaxy designated MoM-z14, that it existed “only” 280 million years after the Big Bang. To put this another way, a detector on the James Webb Space Telescope observing in the near-infrared has shown this object’s light has been traveling to us for 13.5 of the universe’s estimated 13.8 billion years of existence.

Here’s how the image from JWST looks. All of the objects you can see, with the exception of the Milky Way Galaxy’s own stars, which have six long spikes extending from them, (such as the one to the upper left – an effect of the space telescope’s optics) are individual galaxies. To the right of the picture you can see an insert with lines drawing your attention to where MoM-z14 appears among the others.

While this little “smudge” of yellowish light doesn’t look like much, there is one thing about it and a number of other galaxies detected this far back in time that’s unusual. They’re unexpectedly bright. And they’re not just bright, but are 100 times more so than what theory suggests they should be this close in time to the Big Bang. As one could imagine, the big question is why since the stars in such galaxies would not have had enough time for one of the observed elements they contain, nitrogen, to have formed through the evolution of their stars.

Our own Milky Way Galaxy may be able to help provide an answer. Some of the oldest stars in it also show high amounts of nitrogen in them, just like in MoM-z14 and the other unusually bright galaxies from the early universe. A possible solution to these distant examples could be due to the much higher density in their local environment relatively soon after the Big Bang. Such conditions would lead to supermassive stars, which could have produced all the nitrogen observed in those galaxies.

Another feature of such bright young galaxies is they could have been able to help clear out the thick fog of surrounding primordial hydrogen created in the Big Bang. Once this sweeping away of this obscuring material began, it became possible for the galaxy’s light and from other objects to begin the long travel through space to the present day so that it could be observed by space telescopes, such as Hubble and Webb.

For see the ESA press release and photos, follow this link. Also included is a short video of zooming through the images field of foreground galaxies until you reach galaxy MoM-z14.

By: Tom Callen